June 1944: It was the third summer of the war. Unprepared for a two front conflict a few years earlier, by then the nation had retooled at an astonishing rate. In the summer of ’44, it showed. Once Operation Overlord stormed the Normandy beaches, the United States turned out tanks, airplanes and ships at a rate greater than all other nations, combined. Bells rang at Corinth Church (then still located downtown) to alert everyone sleeping that the great invasion to take back Europe from the Nazis had begun.

More quietly, local newspaper articles began to document a rising epidemic. Children in and around Hickory were coming down with polio, the mysterious summer disease that came in two forms. It might attack the limbs of young folks, which was bad. Worse was the bulbar strain that froze the lungs, which was deadly.

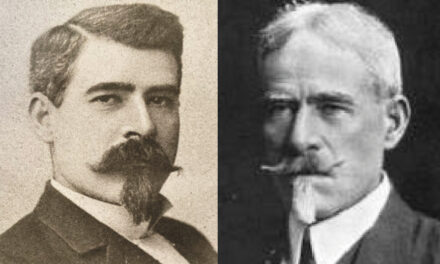

Photo: Dignitaries gather for the 1944 photo op. Nurse Allen on the right. Dr. Hawn, the tall one in back and Dr. H.C. Whims on left. Also, downtown mural, suitable for visiting.

Since 1916, an outbreak had occurred in at least one community in the United States every summer. Researchers struggled to understand why. Conjecture ran wild, since the mechanism that transmitted the poliomyelitis virus was barely understood. With no cure and doctors unsure as to how to treat patients, the disease struck fear into the psyche of America, especially parents.

1944 was not the first time western North Carolina had been visited by infantile paralysis, as it might more accurately be called. About 10 years earlier, a wave blew through. At that time, doctors could offer little comfort. Mostly, they told parents to isolate the child from others and hope for the best.

1944 was not the first time western North Carolina had been visited by infantile paralysis, as it might more accurately be called. About 10 years earlier, a wave blew through. At that time, doctors could offer little comfort. Mostly, they told parents to isolate the child from others and hope for the best.

Fortunately for many, things had changed in a decade. Starting in 1938, President Roosevelt’s initiative to study polio brought attention and funding. On his birthday (January 30), organized events raised money, some of which was dimes pouring into the White House, given by children to support research and care. That’s why the National Foundation for Poliomyelitis was better known as the March of Dimes.

When polio hit the foothills, the National organization was equipped to bring in its expertise. Doctors, nurses, epidemiologists, technicians all came to comfort victims and use the event as a laboratory for cracking the code that would lead to a vaccine. By the end of the month, the national organization was on the ground here, treating patients, asking questions and bringing attention to one of the era’s biggest diseases.

It all happened quickly. The first case was reported on June 1. Within a week, the papers revealed more, right beside the progress of the allied invasion of France. The war always took the headlines, since so many were serving, not just in Europe, but the Pacific as well. However, the rise in cases alarmed local medical personnel to the point that something had to be done to combat it, a very different battle than was being fought overseas.

Catawba County Health Nurse Frances Allen, County Health Director, Dr. H.C. Whims, and Dr. Gaither Hawn, head of the local Nation Foundation chapter got together, created a plan of action, and issued a call to arms.