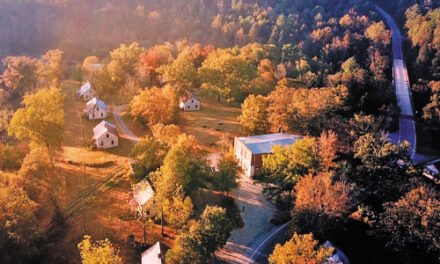

Last Saturday July 6, another odd anniversary took place. For years, over at Reynolda House in Winston-Salem, the home of the R.J. Reynolds family turned art museum, curators shunned any mention of the event that took place there. They wanted to talk about the tobacco industrialist, his family and the art that lines the walls of the place. Only recently have things changed.

Now the museum has an exhibit, called “Two Rings, 7 months, 1 bullet” that traces events leading to that night when the youngest heir of the family fortune, Zachary Smith Reynolds, died under mysterious circumstances at the house. It was either murder, suicide or a clumsy, drunken accident but to this day, 92 years later, we don’t know.

The turnabout likely came over (pardon the pun) an undying interest in the story. Since the case was never solved, fans of true crime come to see where the deed took place and draw their own conclusions. Considered an unseemly chapter of the New South story of the creation of the Reynolds tobacco empire, nobody talked about it publicly for decades.

It’s got it all. Intrigue, money, profligate living, a real ‘lives of the rich and famous,’ in the midst of the early 20th century. Here is how it started.

Photo: Smith Reynolds, and Broadway star Libby Holman

Richard Joshua Reynolds grew up on a tobacco farm in southern Virginia. He had four brothers, one of which went to Tennessee and start his own factory for processing the leaf, until religious conviction convinced him to stop supplying the sinful trade of ‘tobakky’. He went into the metals business and started making a product you may have heard of, Reynolds Wrap.

R.J. had no such qualms. He moved to Winston (before it was linked with Salem), starting his own factory and making a profit. When he hit upon the idea to sell a brand based on “a blend of Turkish and domestic” tobaccos, and call the cigarette Camel, sales skyrocketed. The brand outsold all others by a wide margin and Reynolds became as famous as Buck Duke down in Durham. The money rolled in.

Just as the family moved into to the new house, called Reynolda, R.J. died of pancreatic cancer. His wife Katherine married again, but died giving birth, leaving Smith and his siblings as orphans. With all that wealth, the kids grew up in a loose environment. Since money was no object, parties were always lavish. Which brings us to the night of July 5.

One of the fascinations of the Reynolds boys was aviation. Both Smith and R.J. Jr. (Dick) landed planes on the front lawn at Reynolda. Dick even owned an airline, something of a forerunner to Piedmont Airlines. Smith had just gotten back from a flight across three continents (Europe, Africa, Asia). As a young daredevil, he sought to make the kind of mark Charles Lindbergh did when five years earlier, he flew across the Atlantic. Engine trouble kept the feat from making the same kind of history as the Spirit of St. Louis, but it was still a big deal. For the party, bootleg liquor was flown in from Danville, Virginia.

The party that night included a few friends and Smith’s new wife, Libby Holman. She was a legitimate Broadway star, who headlined two smash hits along the Great White Way. Eight years older than Smith, Libby initially regarded her future husband as having nothing more than a school boy crush on her, but when her entourage went out for an evening of drinks, Smith always paid. His ardor for her finally convinced the Ohio born actress and singer that he was serious. They married six days after Smith’s divorce from the heiress to Kannapolis’ textile dynasty, Cannon MIlls.

Old money in Winston-Salem regarded Libby as an oddity. An artist, an outsider, she was also whispered about because she was Jewish. She brought several of her friends from New York down to Reynolda as she acclimated to a new life with her new husband. He had convinced her to give up acting for a while. Her acting coach, Blanch Yurka was on hand to help Libby plot an eventual return to the stage.

With a mix of southern wealth and New York trendiness, Smith’s last party promised to be an interesting one.