The early days of the Great Depression caught most folks unaware and unprepared for the lean times it brought. Prior, the economy of the 1920s buzzed along as a new, modern way of life permeated American society. All kinds of new modern conveniences became available. Radios killed boredom. Automobiles had mostly replaced horses and mules as way to travel. Electricity had moved from curiosity to necessity, especially in town.

Then came the downturn. Black Tuesday, the stock market crash of October 1929 ushered in a prolonged period of economic distress that would last until World War II.

Hickory tried to combat the Depression in its own way. Some manufacturers kept factories running as best they could. The town adopted the slogan, “Hickory Hums” as a way to say they were taking care of their own. And yet, there was a crime committed that screamed just how dire times had become.

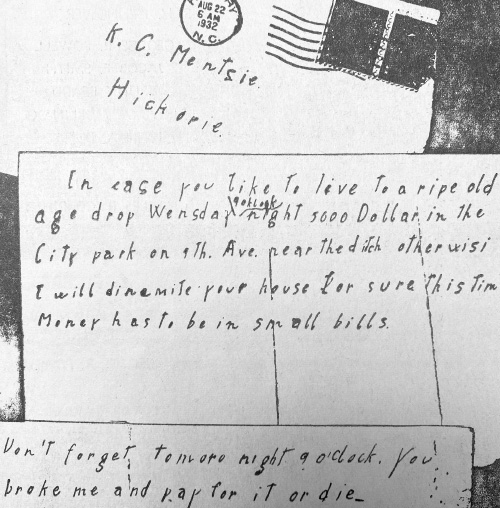

In August of 1932, the president of the First National Bank of Hickory received a letter. It told K.C. Menzies to take $5,000 in small bills to Carolina Park, (now Sally Fox Park) and leave it there in a ditch by the railroad track, in plain sight. If the bank president did not comply, he might not “live to a ripe old age,” warned the writer.

Menzies was not the only businessman to receive such an extortion threat. Two others got similar letters. The second demanded the same amount while the third upped the price to $6,000. Suggestions of death and dynamite were a part of all three.

Immediately, an investigation was launched to find the culprit. Police surveilled the area where the drop was supposed to be made, intently. At the time of the third letter in November, a man walking around the park was arrested, questioned and charged with vagrancy but not blackmail. He was later released.

The letters were thought to have come from the same person “because the words are printed with pen and ink and the same general characteristics of style are evident in all of the anonymous messages,” wrote the Charlotte Observer about the crime. Mr. Menzies received more than one threat. The names of the two other leaders were kept out of print, but were identified generally as “financial and industrial leaders of Hickory.”

Who was responsible? We never found out. Conjecture about the statement, “you broke me and pay for it or die,” suggested the perpetrator felt wronged (foreclosure maybe?) by the bank in some way, but without a guilty party, nothing could be proven. After the plot was revealed, news of the vendetta evaporated as quickly as it came. No person was ever charged with the crime of extortion, ever. Whomever was responsible let the issue go and thanked their lucky stars that they didn’t get caught. They may not have succeeded in reaping the money, but at least they were not doing jail time.

The event came just two years after Menzies became president of the bank. He would go on to serve another 25 years in that position. During his tenure, the First National Bank of Hickory’s merged with Shuford National Bank of Newton and Citizens Bank of Conover to form the First National Bank of Catawba County, which sold to First Union in 1981.

As far as we know, no other assault on a bank in Catawba County ever occurred like the mysterious ‘Blackmail of 1932.’

Photo: Letters from a Hickory extortionist during the Great Depression. Image courtesy of the Hickory Daily Record.