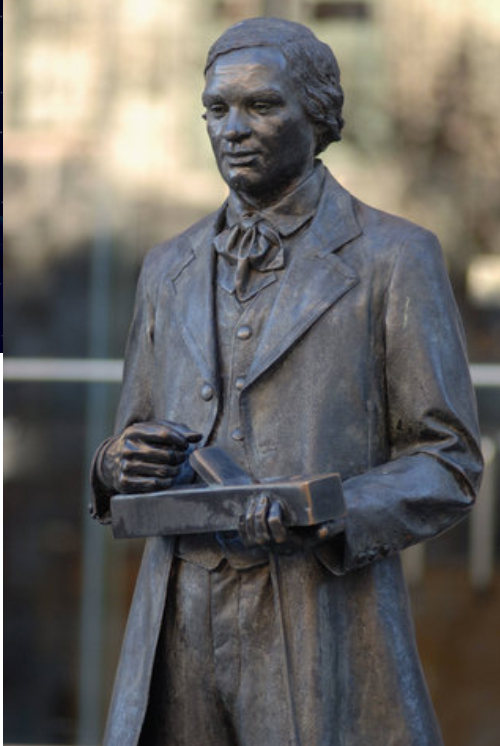

The most famous person to make furniture in North Carolina did not come from the manufacturing tradition. His name was not a brand nor was it associated with any particular company. He was an African-American whose work has been displayed at the Smithsonian and is on regular exhibit at the North Carolina Museum of History in Raleigh. A statue of him stands at that same Raleigh museum. His name is Thomas Day.

Statue of Thomas Day at the North Carolina Museum of History

An artist, businessman, and expert navigator of his times, Thomas Day grew up during the era of slavery. He was a free man of color who built perhaps the best-known black owned business in the Tarheel state prior to the Civil War. His workshop in Milton (near the NC/VA border) churned out exquisite furniture pieces that can be found today in the Governor’s Mansion in Raleigh, on campus at UNC-Chapel Hill, and in upscale homes throughout the state. His career defies accepted beliefs about racial interaction in the 19th century.

Philo Gaither Harbison, Morganton furniture maker

One story about Thomas Day confirms his status as the best at what he did, and that he knew it. A wealthy white plantation owner wanted the furniture maker to craft several pieces for a lavish home. The client insisted Day come there to do his work. Day refused, preferring to build the pieces at his workshop, then hauling them to the home. An impasse brewed. In the end, the buyer relented. Having Day’s work in his home was more important than being able to order the cabinet maker around. The story reveals the value of Thomas Day’s work and his power to control his own life in an era that usually did not afford such agency to a black man.

One curious addition to Thomas Day’s legacy is the fact that Day owned slaves. His use of the enslaved persons may have been as much a way to protect them as work them, though we will never know for sure. He also hired free blacks, as well as whites to keep production going. The output of his shop included mahogany from Africa and one of his specialties was the skilled use of veneer.

The western North Carolina counterpart to Thomas Day was Philo G. Harbison. Much less is known about Harbison. Born into slavery five years before Day died in 1861, Harbison grew up and made a name for himself in Morganton. A 1998 exhibit by the Historic Burke Foundation noted his work as a highly acclaimed designer and builder of “custom-made furniture.” None of his work it thought to have survived, but his reputation has. In addition to crafting furniture, Harbison was also a skilled builder, responsible for the construction of Gaston Chapel A.M.E. Church in Morganton, a “gothic revival” structure, which still stands. During his career, the local press hailed Harbison as “very industrious” and when he took a trip to California, they admitted they were sorry to see him go.

The work of Day and Harbison demonstrate that ingenuity knew no color line. Both defied the conventions of their respective eras, slavery, and Jim Crow to establish their work as important to the tradition furniture making, one that would build momentum for an eventual industry.