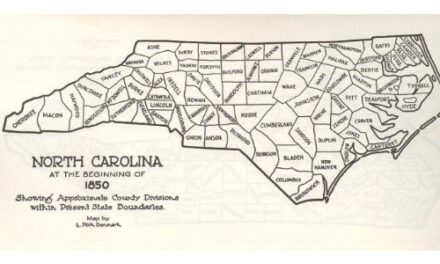

Down on the Caldwell side of the Catawba River, Andrew Ramsour operated a sawmill and iron forge. As a young man in 1849, he took notice of the North Carolina General Assembly chartering a stock company that would spur the building of a bridge to connect the emerging village of Hickory (20 years before it officially became a town) with Lenoir and beyond. Ramseur (who would later change the spelling of his name) and trekked down to Newton to see if anyone was interested.

From four counties, investors came. Not only did Hickoryites and Newtonians inquire about creating a more secure route to bring fresh mountain produce down to awaiting customers, business interests in Lincoln and Gaston counties also wanted to invest. They formed Catawba River Toll Bridge Company, selling 200 shares at $25 per (over $1K in current money) to turn the idea into a paying concern.

At that meeting Andy Ramseur did not buy any stock. Instead, he offered to operated the toll bridge once it was completed. He anticipated the emergence of Hickory as a trading center in western North Carolina and believed that easing transportation bottlenecks would encourage commerce.

At that meeting Andy Ramseur did not buy any stock. Instead, he offered to operated the toll bridge once it was completed. He anticipated the emergence of Hickory as a trading center in western North Carolina and believed that easing transportation bottlenecks would encourage commerce.

Prior to completion of the bridge, the only way to get across the Catawba was by either plunging in or boarding a ferry. One shallow stretch of the river was called the Horse Ford, meaning it could be forded by horse. Water would come up to saddle level and you would get your boots wet, but for a determined traveler it was the quickest way to cross, as long as it had not rained recently.

The other way to get from one side to the other was by ferry. A long, heavy wire strung across the river served as a guide, usually augmented by long poles to also push a flatboat from shore to shore. Ferry boats could carry up to two wagons at a time as it waded the river. To engage a trip, you stopped at the ferryman’s house and paid a fee. If you were on the other side of the river, you yelled until someone from the household heard you and picked you up. The process was slow but if your wagon could not withstand the current, ferrying was the best way to ensure crops would not be washed down the river.

Occasionally, nervous animals bolted the ferry boat as they were being carried across and on at least one excursion, a passenger who tried to get “too fresh” with one of the ferryman’s daughters, got dumped into the water for his impertinence.

Investors banked on the belief that travelers would be willing to pay for the improved service of a permanent ferry replacement. Soon after the meeting on December 22, 1849, work commenced on the building of the Horseford Bridge. After three years, a covered span, placed on eight stone pedestals completed the overpass, allowing protection from rain, wind and snow for travelers venturing to and from the high country.

For 50 years, Andy Ramseur collected tolls from tourists, rovers and farmers as their journey took them down from the isolated hills and into the expanses of the western piedmont. The Catawba Toll Bridge Company proved to be a money-making proposition.

So what happened to that bridge? You guessed it.

Photo: The Horseford Bridge crossing the Catawba.