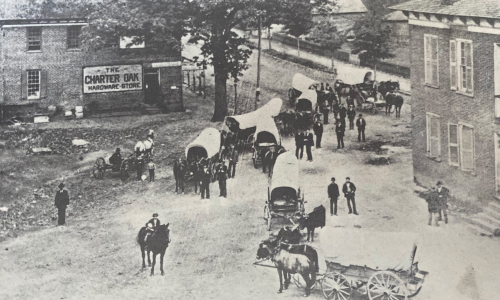

Bang the drum. Shout loudly in the press that something needs to change. And it will. It always has. One hundred thirty years ago a local businessman in Lenoir was doing just that. “Why does not Lenoir grow?” he asked. In the years after the Civil War, the county seat of Caldwell had gone from a sleepy little town to, well a sleepier little town. Penrose Baldwin saw himself as an alarm clock.

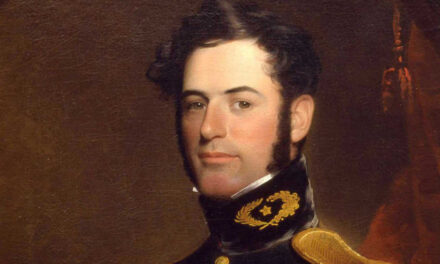

The Chester & Lenoir Narrow Gauge crosses the Catawba River on its way to Lenoir.

With more questions than answers he wanted his fellow Lenoir-ites to explain to him, “Why don’t we have a factory?” Apparently, it didn’t matter what the factory produced. He just wanted a way to employ his fellow citizens, get them off the streets and into productive employment. The question Penrose Baldwin, a pharmacist was asking permeated the era. In Morganton just a few years earlier, an anonymous source was in similar wonderment. However, the effort did not work out for the Burke County seat. The factory brought down from Old Fort ended up burning to the ground in January of 1886, leas than a year after it began operations.

Now Lenoir wanted in on New South industrialization, hopefully with a better outcome. The editor of the Lenoir Topic, W.W. Scott, Jr. took up the cause from his apothecary friend and began to shout that manufacturing could solve of all Lenoir’s problems. After all, the foundation (which came in the form of railroad tracks) had been laid.

In the summer of 1884, citizens heard a train whistle for the first time. The new Chester & Lenoir Narrow Gauge Railroad brought the outside world to Lenoir. The line came directly from Hickory and followed the same road bed it does to this day, right alongside US 321-A. For Scott and his readers, it was a real sign of progress. Once the train whistle blew, could a factory whistle be far behind?

Downtown Lenoir in the days before industry came to town.

Like water from a leaky faucet, Scott peppered his paper with jabs. “When the present astonishing demand for carpenters in the dwelling business line ceases there ought to be at once more work to keep them busy in another line. We ought to have some kind of factory business going in Lenoir. The town must have it to amount to anything. We do not see why we have not had one before now, and not one but two, three, a half dozen,” opined Scott, carried away with the possibilities. He used a variety of tactics to help wake the slumbering citizens of Lenoir. Sometimes he could be longwinded. In another edition, he was succinct, writing simply, “Talk factory.”

W.W. Scott had the perfect combination to change the course of history. He mated a cause (industrialization for Lenoir) with a mouthpiece (The Lenoir Topic). Soon he settled on the idea that it was a furniture factory Lenoir needed. Like D.A. Smith in Old Fort, Scott saw the abundant forests to the north and west of Lenoir as the perfect harvest for his hometown’s ambition. But could he convince his readers? Scott intended to try. Next week we shall see how well he did. A clue: never underestimate the power of the press and an idea whose time had come.