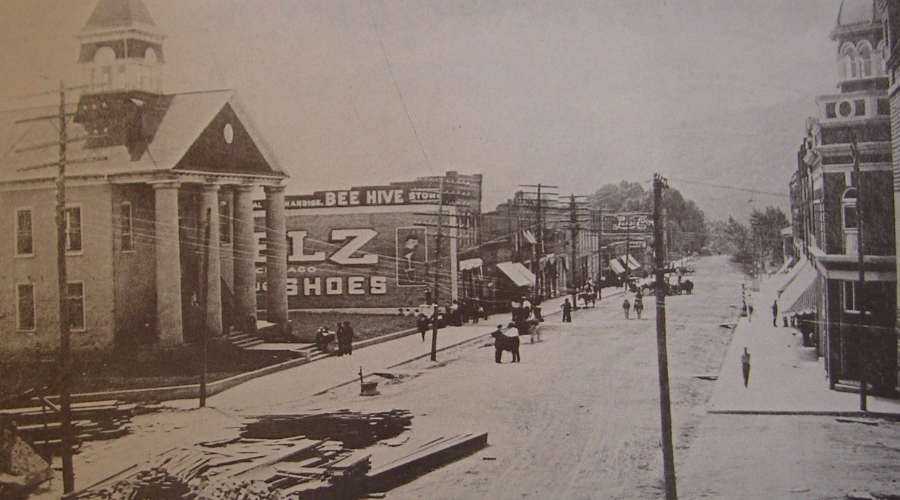

It’s hard to imagine an entire city being erased, only ashes left where once a center of commerce and community stood. Some called it the “saddest day that ever dawned upon Marion.” On that autumn morning, the county seat of McDowell County found itself reduced to one store and the courthouse, both brick, the only survivors of a devastating fire.

Just before noon on Sunday, November 25th, flames broke out in an old frame building, known by local folks as “the Ark.” A high wind was blowing from the northeast, which carried the blaze from one building to another. It only took about three minutes for the fire to spread to two more buildings with the other wooden structures along Main Street just waiting for their turn. After burning down the town, the inferno spread to nearby Mt. Ida, lighting up the sky until daylight. The glow could be seen all the way to Morganton.

In 1894, Marion had no fire department and no water works, so citizens had to form a bucket brigade to combat the threat. The effort was no match. A number of people were overcome by the smoke, requiring medical attention. The wells from which townspeople drew water were quickly depleted and the attempt, though valiant, proved futile.

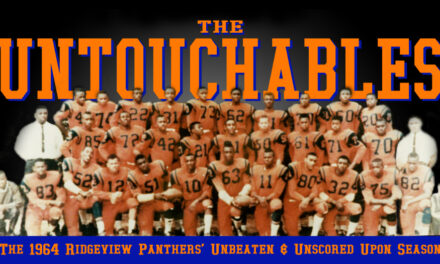

Rebuilt downtown Marion after fire that destroyed the city. Only the courthouse and a brick store withstood the flames.

Rescuers were able to save everyone, including 27 prisoners who were in the county jail that Sunday morning. Their “frantic screams” at the “cracking over their heads” brought out a whole brigade of volunteers to get them out, including one guy who was awaiting trial for murder. He was transported to Rutherfordton but another prisoner got away in the confusion.

While the town could save its people, it could not save the structures they built. Every store, every home, every warehouse in the downtown district (minus the brick store of J.C. McCurry and the courthouse) were gone. A wooden street bridge over the Southern Railroad tracks caught fire and collapsed, delaying help at the crucial hour. According to one report, “the whole population, nearly was on the street fighting fire and carrying out goods.” A good portion of the families living in town (about 70 persons) was rendered homeless.

When the smoke cleared, the damage was worse than imaged. Estimates of the destruction totaled $200,000 ($3.2 million in early 21st century money). Only about six percent of the loss was covered by insurance. As the Asheville paper noted, “some will be able to rebuild, some will not.” Throughout the state, the fire in Marion put every town on the alert. If they didn’t have a fire department, they needed to get one. Fire was a constant threat to many downtown districts. Just the year before, part of Morganton had burned. Ten years after the Marion fire, Drexel Furniture would suffer substantial losses from fire, which was just the first of three such incidents. In fact, a fire just three days before the big one burned down the livery stable in Marion, taking eight horses with it.

Five days after the catastrophe, with some embers still smoking, merchants began the process of rebuilding. A hotel outside of town fed people, the Marion paper put out an issue and the town struggled to get back to business. The people of Marion called it the “greatest calamity that has ever befallen any town in North Carolina,” and they were likely right, in terms of property. However, in terms of lives lost, the toll was light. If there was another “benefit” from the tragedy, it was that Marion learned the lessons of the fire. When folks built back, as one observer noted, “brick and water are the material.”

Down the mountain a ways in Newton. F.M. Williams described the incident as “a severe blow to one of the pluckiest towns in western North Carolina.” A town reflects the collective characteristics of its people who never know how much pluck they’ve got, until they get hit by the severe blow.