The legacy of alcohol that came from Hickory Tavern would not be complete without continuing the story into the Great Depression, when the nation went back to allowing tax-paid liquor to be consumed by age-appropriate Americans. If booze was legal, why did the bootlegging business continue?

In a word, taxes. Moonshining was a long standing tradition in western North Carolina. In one survey, the state was the place where the best was made, not necessarily for its taste, but because it was the safest, or least likely to poison those who took a swig. Many old-time moonshiners, men like Elmore Lippard, were steeped in the tradition. He began his career as a whiskey maker in the days when he brought his product to market by horse and wagon. He was once arrested in downtown Hickory, though he declared he was there to buy, not sell.

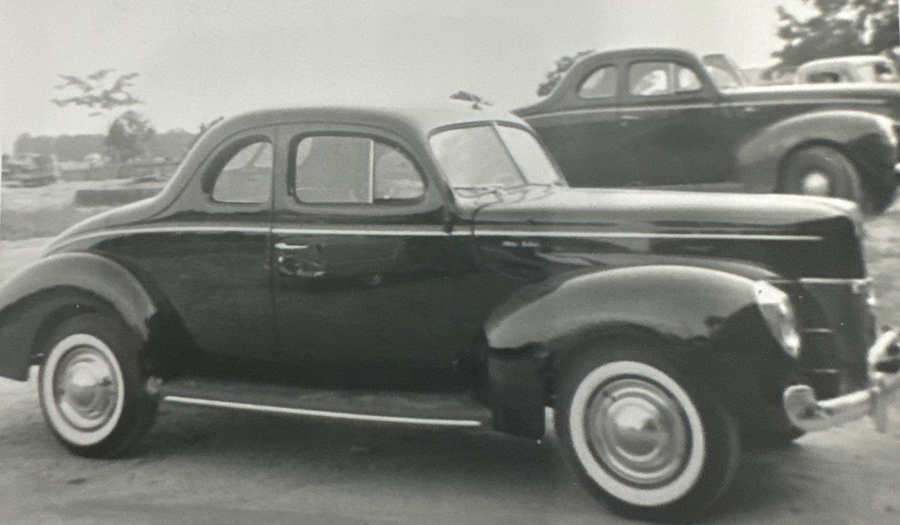

Elmore’s sons and grandsons took on the family business in a more technically advanced way, using automobiles to deliver whiskey instead of a horse. The most famous of them was Bud Lippard. He became a regional folk hero, eluding the law with his expert driving and a car more powerful than anything the police had. He epitomized the intrepid driver, serving as the prototype for the coming of stock car racing.

Photo: A Ford used for bootlegging purposes in western North Carolina. Thanks to Andy Killian for use of the image.

Bud Lippard was also a mythical individual because he seemed to get out of trouble as fast it caught up with him. In all likelihood, his powerful customers in Charlotte tilted the balance of justice in his favor, although much of that is conjecture.

Bud was too busy making runs to Charlotte to engaging in racing for racing’s sake, but a number of drivers did so in the years before World War II at the Hickory Fairgrounds, located in those days around where Hickory High School now stands. After the war, competitions resumed, first at North Wilkesboro Speedway and then in 1951, at Hickory Motor Speedway.

Racers like Junior Johnson got their start on those tracks, and in Junior’s case, he actually mixed driving for sport and business. Arrested once for rumrunning, he pulled a stretch of a little less than a year before returning to competitive racing and making a name for himself in NASCAR. His father, Robert Glenn Johnson, Sr. was one of those more traditional moonshiners. He spent almost a third of his life incarcerated for making mash while his son went onto prominence as a pioneer of stock car racing.

Those early drivers, both on the road and on racetracks took chances that have become legendary. One March 1948 night in Statesville, Harvey Combs was driving through town when the police spotted him. The driver tried to elude his pursuers by ducking through Mitchell College. It almost worked. Heading out of town, law enforcement was back on his trail. Combs swerved to cross a bridge, tipped over and spilled the whole mess, 120 gallons of white lightning, his car, and his freedom.

Stories like that are the stuff of movies. Thunder Road and the Last American Hero, which comes from an article of the same name about Junior Johnson, can take you on that ride.