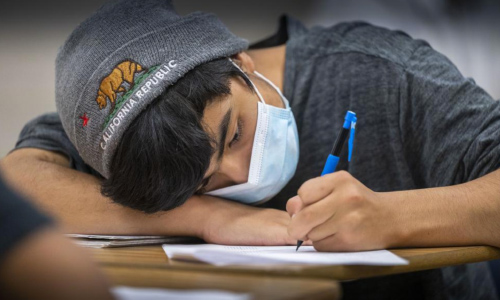

(AP) – Despite a year of disruptions, students largely made academic gains this past year that paralleled their growth pre-pandemic and outpaced the previous school year, according to new research released Tuesday from NWEA, a nonprofit research group that administers standardized tests.

Gains across income levels partially closed the gap in learning that resulted from the pandemic, researchers found. But students in high-poverty schools had fallen further behind, making it likely they will need more time than their higher-income peers to make a full recovery.

The results are a measured sign of hope for academic recovery from COVID-19. But sustained effort and investment in education remain crucial.

“These signs of rebounding are especially heartening during another challenging school year of more variants, staff shortages, and a host of uncertainties. We think that speaks volumes to the tremendous effort put forth by our schools to support students,” Karyn Lewis, director of the Center for School and Student Progress at NWEA, and the study’s co-author, said in a statement.

The study used data from more than 8 million students who took the MAP Growth assessment in reading and math during the three school years impacted by COVID. Those numbers were then compared with data from three years before the pandemic.

The study found that if rebounding occurs at the same pace it did in the 2021-2022 school year, the timeline for a full recovery would likely reach beyond the 2024 deadline for schools to spend their federal funds.

For the average elementary school student, researchers projected it would take three years to reach where they would have been without the pandemic. For older students, recovery could take much longer. Across grade levels, subject and demographic groups, the exact timeline can vary widely and researchers found most students will need more than the two years where increased federal funding is available.

Some of the most successful interventions for students involved increasing instructional time, ranging from more class time, intensive tutoring, or high-quality summer programming, said Lindsay Dworkin, senior vice president for policy and communications at NWEA. But those initiatives can be costly and complex, and districts may hesitate to implement them when recovery funds have a fast-approaching deadline to be spent.

“The funding expires in such a short amount of time that districts are really struggling with, ‘What can I do that will be big and impactful and I only need to do for two years?’” Dworkin said in an interview. “I think if they knew that there would be more federal money coming and that it would be sustained, that would make all the difference both in the kind of creativity we would see from states and districts.”

Dworkin also said that while the study looked at national trends, understanding the unique and specific local context was essential to figuring out how to best support children in schools. In addition to variation across student groups, districts that share similar characteristics, such as demographics and poverty levels, still showed large variation in student outcomes.

“If you are a district leader, there’s just no national story that is going to tell you enough about your district context, without the hard work of digging into the data and understanding what it says and then tailoring the interventions to match,” Dworkin said.

Angel Cardenas, a freshman at Hiram Johnson High School