Have you ever thought about becoming a hermit? Probably not seriously but there have likely been days when your luck was so bad that you may have considered it, even for a moment. As a substitute, you may want to check out a fellow North Carolinian who actually did.

His real name was Robert Harrill, but most knew him by where and how he spent the last portion of his life. He described those days as some of his happiest. After years of trying to carve out for himself a conventional life, he left it all behind to find bliss as the Fort Fisher Hermit.

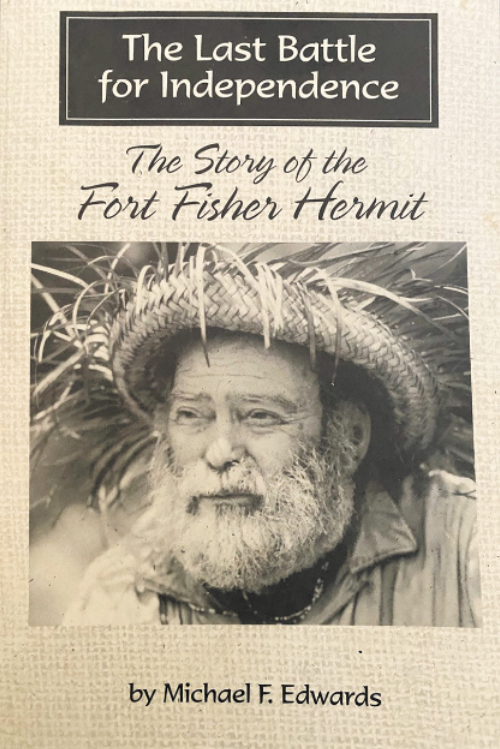

Photo: A primer on what it would be like to abandon your life and move to the coast with no money, just a desire for total freedom.

Michael F. Edwards wrote about Harrill in an excellent book, called The Last Battle for Independence: The Story of the Fort Fisher Hermit. In it, he details the life of a man who abandoned the struggles of everyday existence to find freedom, living the life of one choosing to shed what all the rest of us consider the necessities of life.

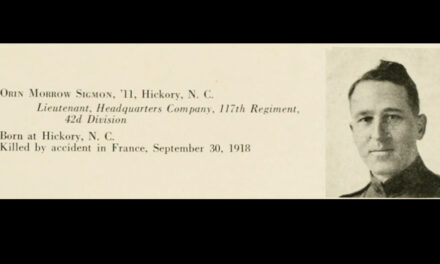

Born in Shelby in 1893, Harrill spent time doing what every American is expected to do. He married, fathered five children and got work as best he could. He served his community as a magistrate, but instructions to look the other way when it came to the behavior of “important people in town” stirred a resentment toward society in him that he never forgot. In fact, it turned him away from participating. During the Great Depression and doing his best to make ends meet, Robert began to retreat from the world. Divorced and own his own, he migrated to the coast of NC. He had been there before with his family and enjoyed it as a place of great abundance as he fished for his family’s supper. After Hurricane Hazel devastated the region in 1954, he landed at Fort Fisher, site of a Civil War earthen fort, and decided to stay.

For almost 20 years, he lived off the land and sea, squatting in an abandoned military bunker. Despite efforts by the Army and the state to evict him, he made it his home. In fact, Harrill became became something of a tourist attraction. Throughout the 50s and 60s, he attracted up to 15,000 annually, each throwing a few coins into his frying pan, which kept him going. Once word got out, folks crowned him the Hermit of Fort Fisher. However, it wasn’t all tourists and sunshine. Some bullied and abused him, which only hardened his attitude toward the world. Yet, he persisted, refusing to trade his days on the beach for a more conventional existence.

Robert Harrill corresponded with the Governor, who said he wanted to go fishing with him (he never did). The Hermit invited the Premier of the Soviet Union to come see him (another no show). Technically, he was not a hermit since he welcomed those who came to gawk at him, including the book’s author. As a 9-year-old kid, Micheal Edwards remembered visiting Harrill in his habitat. After the Hermit’s death in 1972, some who admired the ‘Hemingway like’ character and his abandonment of convention, formed the Hermit Society. Over 600 members strong, they have since sought to honor the “independence, self-reliance, Nature and ‘common sense’” of what can only be described as one of North Carolina’s most “controversial and interesting characters.”

For those of us who lack the fortitude (or whatever you might call it) to follow Robert Harrill’s example, this book offers a glimpse into what it would be like to defy society and walk an individual path.