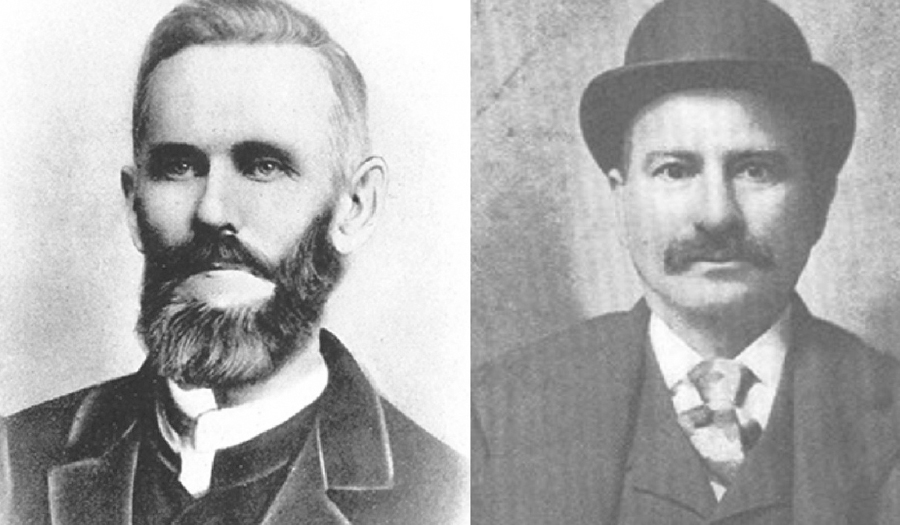

2023 marks a major centennial for Lenoir-Rhyne University. Granted, the school is much older than that. The origins go back to 1891 when it first became an institution of higher learning. Walter Waightstill Lenoir had previously donated land a mile northeast of Hickory’s business district for use as a college. Twelve students were admitted that first semester and soon, Highland College was renamed for Lenoir’s donation of 56 acres. Four area Lutheran pastors came together to run the facility.

1923 was the year that the school fully became an institution in the community of Hickory. In the years after World War I, Lenoir College as it was called then, was growing. Leadership sought to raise funds for several projects that would accommodate students. Facilities like a gymnasium and dormitories were needed. They appealed to cotton mill owner Daniel Rhyne to contribute $850k “for the needed expansion of the institution.” He said no.

The two namesakes of Lenoir-Rhyne University, W.W. Lenoir and D.E. Rhyne. Lenoir died before the school opened. Rhyne helped the school grow, almost out of Hickory.

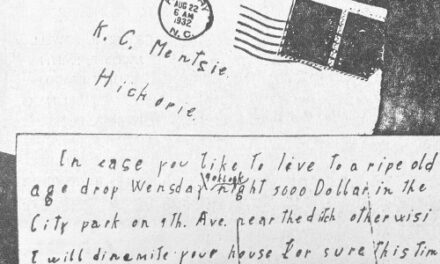

Rhyne didn’t mind contributing but he wanted other wealthy citizens in the area to join in and share the responsibility. He did have an alternative offer. Suggesting that if the college were renamed Daniel Rhyne College, he would write them a check for $300k. It almost worked. The governing board agreed to the proposal, but alumni said no. They wanted to retain some portion of the identity of the school they loved. A compromise was struck that hyphenated the name. Rhyne agreed and the change was slated to take effect in the fall of 1925. Everyone happy. Crisis averted, right?

Not really. Back in 1916, when Claremont Female College closed its doors, Lenoir College was the only place of higher learning in town. In addition, 1923 was the same year that down in Newton, Catawba College shut down, moving its location from the county seat to Salisbury, where it planned to reopen during the same fall semester of the Lenoir-Rhyne name change.

In those days, a town with no center of post-secondary education was considered as inferior. Colleges began to emerge as a sign of a city’s importance. In addition to attracting students in town and jobs for graduates after, a school like L-R offered a variety of activities in which local citizens could participate. Academic events like debates were popular, but sports offered the best draw. Rooting for the Bears became a distinctly Hickory activity, be it baseball, basketball or the newest spectator sport, football. In 1924, the school built Cline Gymnasium. It has since been demolished but at one time it served as a hub of activity on campus.

So where was the theft? Seeing how popular and how important Lenoir-Rhyne was to the fabric of Hickory, it’s no surprise that other towns in the area began to conceive schemes to poach the college and move it elsewhere. What town would engage in such sinister shenanigans? And who might be their accomplice in the dubious effort to steal Lenoir-Rhyne from its city of origin? Well, it was none other that the school’s savior, Daniel Rhyne, playing a part in the move. In addition, a whole list of cities lined up to welcome the Bears to their community, namely Gastonia, Mt. Holly and Lincolnton. Next week, how each maneuvered to try to take it.