A woman in Hickory once ordered furniture from Sears, Roebuck and Company, the mail order giant of the 20th century. When the suite arrived, she was shocked to discover that the furniture she saw in the Sears catalog was made in her own hometown. She sent it back immediately with a letter of contempt. She expected quality furniture from a national company, not the output of a western North Carolina furniture maker. In other words, she regarded the furniture made in her hometown inferior and not worthy of her home.

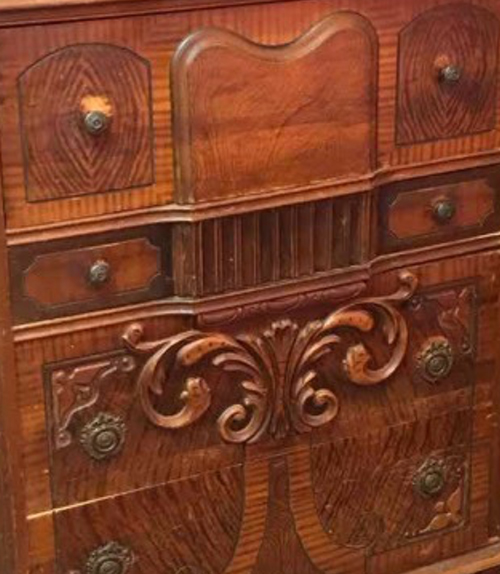

Front of a dresser made during the Great Depression. The ornamentation disguises the poorer quality of the wood and workmanship used.

There were euphemisms for the kind of furniture many people (not just the consumer in Hickory) believed came out of local factories. They called it “borax.” If you remember that word as a type of soap, you are on the right track. At one time, boxes of borax soap included a coupon for other household goods. Things like drinking glasses were actually inside the box, while bigger ticket items like furniture used coupons. If you got a ‘prize’ in the box of soap it was considered low-priced.

Instead of calling southern furniture cheap, the genteel of the South looked for another word. Borax fit the bill for a product considered to be cut-rate, flashy, and poorly made. In the industry, manufacturers had another phrase. They called it their “promotional” lines. Advertising the cost of the more inexpensively priced furniture served as a way to draw folks into the store.

Ralph Bowman, one time president of Hickory Chair said buyers of promotional furniture were lucky if the stuff lasted ten years. Another joke around the furniture industry was an exchange of telegrams between retailer and manufacturer. The store owner wired the factory with a question. “Bedroom suite just arrived, but don’t know whether to set up the suite or the crate. Advise.” A wry response instructed, “Set ‘em both up, put ‘em in your window and reorder whichever one sells.”

Borax furniture was generally made of inferior wood, mostly gum and poplar. To hide the shoddiness, veneer was used. Machine routing “carvings” were added to disguise the quality. One observer described it as “bulging with waterfalls, swirling with synthetic inlays, slopped up with shading and gopped up with gingerbread hardware.”

Southerners had to live with the slur on their product. Some of it came from a general attitude about the Appalachian South, that everyone was a ‘lazy hillbilly’ and by extension, the products they made were third-rate. But manufacturers knew the market and made money on the budget lines, especially when the Great Depression hit. In their advertising, companies asserted that “good furniture is not expensive furniture.”

One company just could not take the connotation. In the middle of the 1930s, Drexel made a conscious choice to leave the promotional market to its competitors. In 1937, the company upgraded its lines. The new strategy offered the opportunity to coordinate an entire house (living, dining, bedrooms) with a harmonized style instead of just one room. The move set Drexel apart and positioned it for a better reputation as the entire North Carolina furniture industry came into its own after World War II.

In one form or another however, borax furniture remained a part of most furniture catalogs to this day. Styles changed but the need for a line that everyone could afford remained a choice for manufacturers. One factory owner swore by it. He said that making higher priced furniture only cut some buyers out of choosing his product. He wanted everyone to be his customer.