One of the most important authors to come from North Carolina is David Walker. Who is that? you ask. You are not alone, but it is important that we examine and remember his work, brief though his literary career was.

One of the big mistakes of interpreting history is seeing everything that happened as inevitable. It seems that the American Civil War was inevitable, and yet we look back on it as a tragedy that need not have occurred. The words of David Walker served to ignite the need for change, even though he died 30 years before the war started.

David Walker was born in Wilmington around 1796, to an enslaved father and a free mother. Since the law of the time stipulated that “condition of the child goes with the mother” he was born free. The law was intended to be used quite oppositely, as in when a slaveowner raped an enslaved woman, the child was born into bondage by law.

Though free, Walker saw much of the torture associated with enslavement. He once witnessed a son having to whip his mother until she died. His freedom allowed him to move north, eventually settling in Boston. A keen observer, he began to contribute to the nation’s first abolitionist newspaper, Freedom’s Journal, becoming a well-known writer.

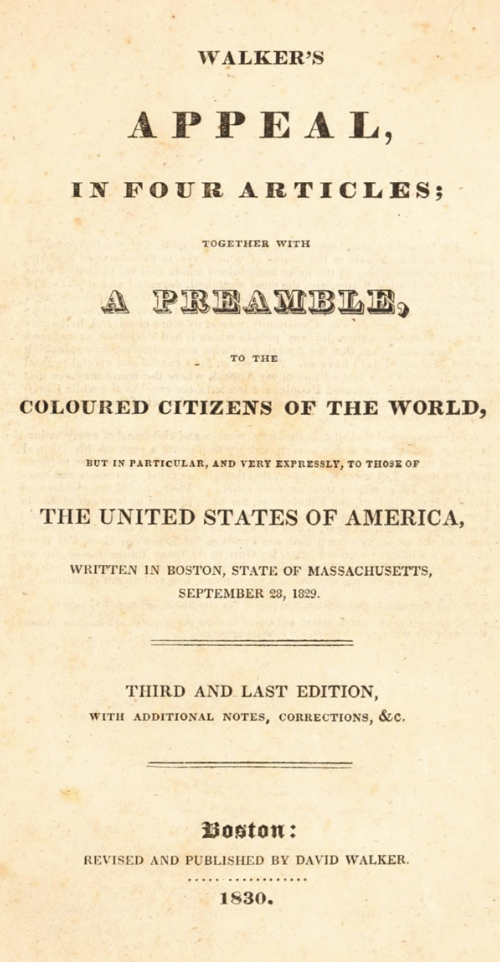

In 1829, he wrote David Walker’s Appeal in Four Articles: Together With a Preamble to the Colored Citizens of the World But in Particular and Very Expressly to Those of the United States of America, a collection of his arguments against slavery. In it, he refuted all suggestions by founding father Thomas Jefferson that the races were unequal. He advocated immediate and total revolution to overturn a system that he regarded as unchristian, being a devout believer himself. His words were so direct and inciting that the white leader of abolitionism of the era, William Lloyd Garrison called Walker’s work “radical” and objected to its release.

Walker matched the power of his argument with a genius move in distribution. In Boston, Walker owned a used clothing store, frequented by sailors. Many of them traveled to ports in the South. In selling clothes to his nautical customers, he sewed copies of his Appeal inside as a way to transport his pamphlet to the intended audience, those still enslaved. He wanted them to understand in no uncertain terms how barbarous the system was and how unfairly they were trapped.

The plan worked. Within weeks of publication, copies were found from Virginia to Louisiana. Slave owners furiously put a bounty on David Walker’s head, $3000 dead, $10,000 alive. He anticipated as much writing, “I may be doomed to the stake and the fire, or the scaffolding tree, but it is not in me to falter if I can promote the work of emancipation.” In his work, he called upon the enslaved to recognize their contribution to American society, refute any assertion of white superiority and resist all efforts of enslavement. One historian called it “the most notorious document in America.”

Just after the publication of Walker’s third edition of the Appeal, he died in Boston at age 33. Given the price on his head, many believed that he had been poisoned. However, tuberculosis was more likely the cause. Even after his death in 1830, the Appeal lived on and future Civil Rights leaders cited it as inspiring. Frederick Douglass, Nat Turner, Malcolm X, and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (Garrison too) acknowledged David Walker’s brave words as important to their own subsequent work.

Yes, his career was short and he had only one title to his name, but what a transformative work it was. Boldly and eloquently defining his position in antebellum America, David Walker’s writings changed the nation for good.

Photo: No real credible image of David Walker exists, but his words are immortal.