In 1960, local historian J. Weston Clinard made an insightful observation about his hometown. He said, “The people of Hickory did not have to seek help from neighboring towns when there was a large or small job to be done. The first settlers had among them skilled laborers, artisans, craftsmen and mechanics. The aggressiveness of this settlement, from the time of its inception, attracted others, who were experts in their lines, to come here and make their homes.”

In his weekly Hickory Daily Record column, Clinard pointed out the strength of his home came from being a place where everyone was appreciated for their contribution. Though they arrived as outsiders, if newcomers demonstrated drive and skill, the local establishment welcomed them. Together, they created a unique culture, building an economic hub for the region.

The prime movers of what we would consider ‘Old Hickory’ infused their work with a proactive spirit. Whether the businesses they started are still around or not, or the structures they built still stand (some do, some don’t), they set the stage for future success with an unrelenting energy.

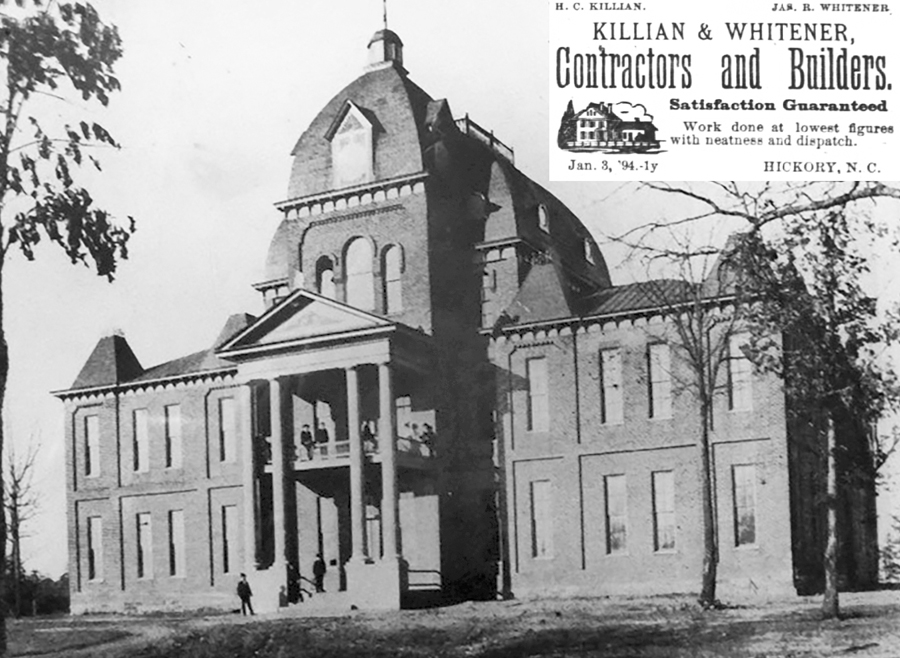

Photo: Old Main and a calling card from its builders.

A town so bent upon forging a path to the future didn’t worry much with where it had been. They were more concerned with where they were going. These were, as Clinard noted, aggressive people. Among them were two family names of longstanding in Catawba County, Killian and Whitener. Henry Killian and James R. Whitener were builders. For the first project in their partnership, they took on the mammoth construction of one the grandest edifices ever to be seen in Hickory.

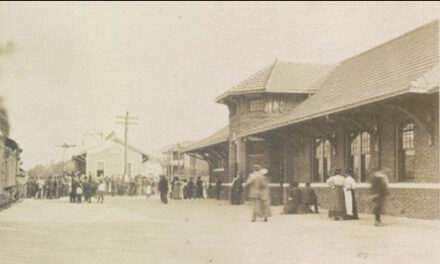

In the early 1890s, Lenoir College was under initial construction. Killian and Whitener bid for and won the job of sculpting a centerpiece for the campus, a commencement hall that housed the president’s office, the library, an auditorium, several classrooms and some dormitory rooms. Though one of the carpenters fell during its construction (not fatally), it was announced in March of 1893, “Killian and Whitener, contractors, have obligated themselves to complete Commencement Hall of Lenoir College by May. It is to be magnificently finished.” They met the deadline and by all accounts their creation was impressive.

The finished complex eventually became known as Old Main. Clinard remembered the structure as “quite unusual for this section.” He pointed out that the “dome shaped roof over the main part of the building” could be “seen for miles away,” making it a shining example of what an aggressive community could do in putting its best foot forward.

For over 30 years, Old Main served as the jewel in the college’s crown. Commencements, plays, events of all sorts were presented there. Then came the night of January 6, 1927. A fire of indeterminate origin started in the library some time after midnight. By morning, Old Main had been reduced to rubble. The blaze took books, records and the focal point of the recently renamed Lenoir-Rhyne College. No one lost their life, though some students were reported to have thrown their trunks out the window to preserve belongings.

Despite the damage, students were back in class the following day and college president H. Brent Schaeffer issued a statement that announced, “out of the ashes will rise the new buildings so vitally needed” to continue the mission of education. Instead of replicating the domed grandeur of Old Main, college leaders opted for the more conventional structure that greets you today at the end of the campus Quad, the Daniel E. Rhyne Building.

Despite setbacks, those aggressive people could not be stopped.