The founders of this nation and those who came after, give us reason to celebrate 247 years of self government. Starting with an ingenious framework, we’ve put the basic idea into the hands of successive generations to reshape our American system as needed. Last week I mentioned Romulus Linney, known locally as the Bull of the Brushies. During his era (turn of the 20th century) he said, “a vote governs better than a crown,” words so profound you should be able to find them carved into a structure on the campus of Appalachian State University, a school he helped fund. More on him next week.

These formative leaders have taken serious the job of guiding democracy through centuries of use. For the most part, they have adequately done their job, but they did not always conduct themselves in a statesman-like manner. Quite often, we give them more credit than they deserve.

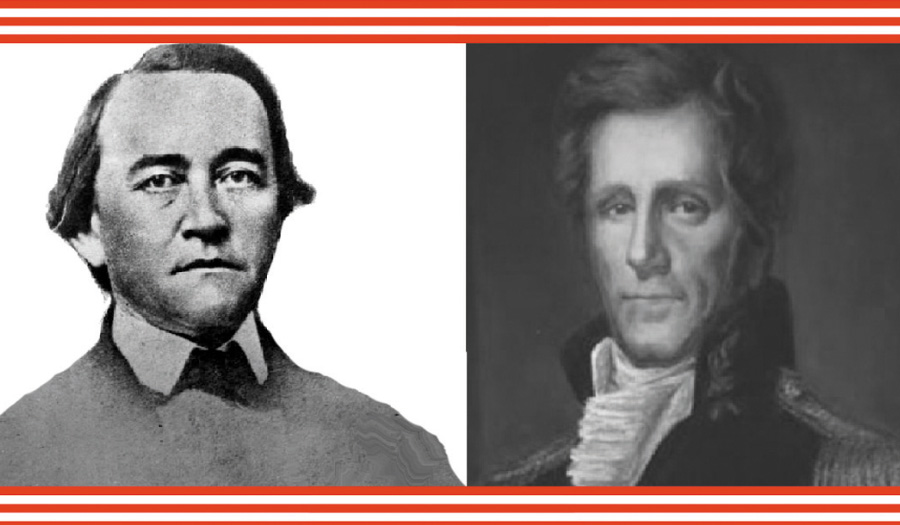

Waightstill Avery was a lawyer from Morganton. His home, Swan Ponds Plantation now features a house built by his son. Avery served as North Carolina’s first attorney general and was a colonel in the Revolutionary War. By the 1780s, he was much more famous than a young upstart lawyer he found himself opposing in a courtroom in Jonesboro (now Tennessee, then NC). Born somewhere along the NC/SC line and trained as an attorney in Salisbury, you might have heard of the then 21-year-old legal practitioner. Andrew Jackson.

Photo: Waightstill Avery and Andrew Jackson, keepers of the democracy.

Avery carried with him in his saddlebags a copy of Bacon’s Abridgment, aka The Elements of the Common Laws of England by Francis Bacon, a book upon which much of American law is based. Riding the circuit from courthouse to courthouse, Waightstill Avery used the reference work to cite precedent. In August of 1788, Avery argued a case against Jackson, 26 years his junior. The two had a cordial, even friendly relationship until the young lawyer made a “facetious remark” about Avery’s repeated reliance on the Bacon book in court. Avery shot back that Jackson had “much to learn” from such a volume. Jackson took the patronizing remark as an insult and looked for a way to retaliate.

Burned, Jackson devised a practical joke to get back at his adversary. He substituted a slab of actual bacon, carefully wrapped, for the law book and when Avery attempted to reference Bacon’s Abridgment during a session of court, the elder counsel pulled out a side of bacon. The man who would go on to become the seventh president of the United States thought the prank was funny. Opposing counsel did not. Hot words were exchanged and Jackson proposed a duel to settle matters.

He wrote Avery, “you have insulted me in the presence of a court and a large audience.” The whole affair had embarrassed Jackson, who went on to write, “I therefore call upon you as a gentleman to give me satisfaction for the same.”

The showdown took place with pistols as the weapon of choice, on August 12, after the day’s session of court had ended. Avery objected to dueling but accepted the challenge as the only way to defend his honor. He allowed Jackson to fire first and when the projectile missed, Avery walked over and lectured Jackson as a father might do to his son, this time out of earshot of spectators.

The incident speaks better of Waightstill Avery than it does of Andrew Jackson. It took bravery to see how accurately Jackson might aim and wait for the result. Yet Jackson was a pugnacious guy in his own right. When he died after two contentious terms as president, he still had lead in his body from previous duels. Beyond statesmanship, it’s another essential of the American character, guts.