An idea who’s time had come. W.W. Scott was sure he had a cure for all of Lenoir’s problems in the 1880s. Like many small southern towns in the wake of the Civil War, Lenoir could not overcome the losses brought on by what was (and remains), the most devastating conflict in the history of the United States. In the aftermath, the economic trend of industrialization had left many agrarian towns like Lenoir without a way to progress.

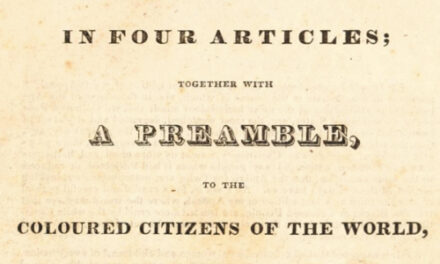

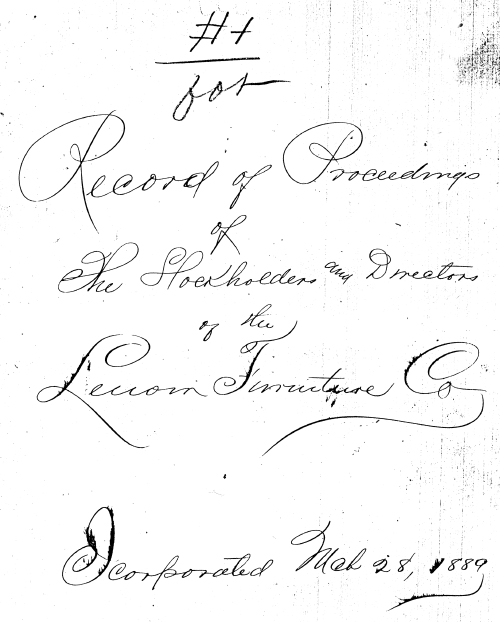

Incorporation papers of the Lenoir Furniture Factory, the first permanent contribution to an industry for which the region became known.

In the pages of the Lenoir Topic Scott went on a crusade. The town needed a factory to become part of the modern world. He pleaded, he insulted, he reasoned, he joked, but for three years, starting in 1886, his vision was slow to find acceptance. Scott’s solution was communal and simple. If everyone subscribed to the idea with small contributions, funds could be raised to start a factory. After a lot of editorials, subscriptions began to come in.

A community meeting on March 28, 1889 brought a raft of speeches (and an extra $1000) to encourage citizens to pool their resources for common cause. “Let the good work go on,” implored Scott as the campaign to industrialize Lenoir gained speed. But it began to dawn on Scott and his fellow investors (he actually put his money where his mouth was) that they knew nothing about what they were trying to accomplish. So, for guidance, Scott published an article entitled, “How to Build A Factory.” Their blissful ignorance could not curb their enthusiasm.

In that era, much of Lenoir looked to its leading citizen, George Washington Finley Harper for direction. His family was the wealthiest in town, having given land for much of what is downtown Lenoir today. Everyone referred to him as Major Harper, a show of respect for his rank in the war. G.W.F. liked the factory idea and was willing to invest, but not without the support of his fellow citizens. Harper was known as a mentor to many young men, not the least of which was a clerk at Harper’s store. Around town they called him “Barny”. One day he would become Harper’s son-in-law and and known to the furniture industry as John Mathias Bernhardt.

When the furniture factory became a reality in Lenoir, Bernhardt was asked to lead it. After a stint at Davidson College (also G.W.F.’s alma mater), Barny worked as a land agent for the federal government in Oregon, giving him valuable experience in wood. He returned to Lenoir in time to be the one to take the helm of the new factory. By the spring of 1889, Bernhardt was the busiest man in town. He oversaw construction of the Lenoir Furniture Factory, as well as designed the pieces made, bought timber (his specialty) and promoted the success of the idea. He also traveled the Midwest, selling the output of his factory.

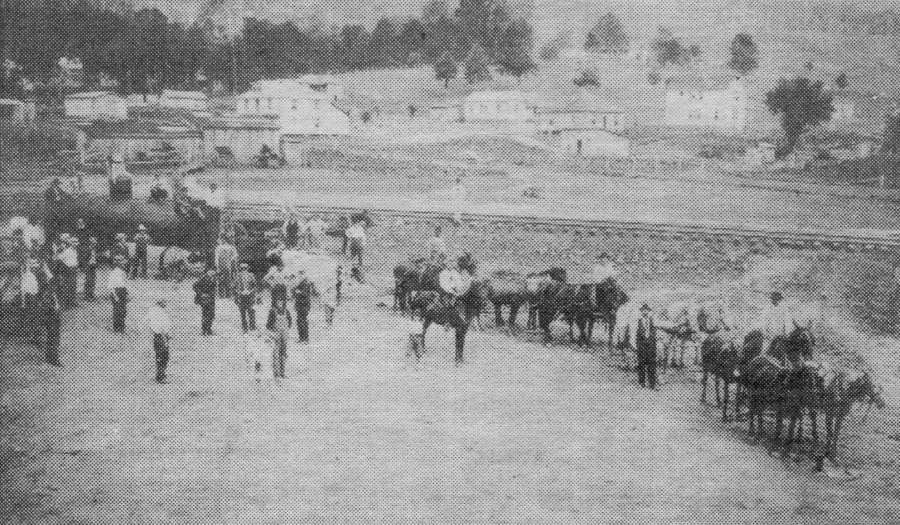

The day the boiler came to Lenoir. Bernhardt and his fellow citizens haul the power source to the new factory to get operations underway.

In an interview with W.W. Scott, Bernhardt was bullish. “I am very much encouraged about the enterprise and believe it will be the best paying business in the country,” he assured readers in Lenoir. That facility would one day become part of the Broyhill chain of factories, while Bernhardt would go on to start his own company that still operates as a family business and Major Harper (along with his son George) would jump in with his own operation with Fairfield Chair, a firm that celebrates its centennial this year.

What Scott started, Barny and the Major made happen. From there the western North Carolina furniture industry was born.