Long before the nation tried the grand but failed experiment to keep beverages of alcoholic content from citizens, folks in Hickory debated the question. Those for open access to beer, wine and whiskey were known as ‘wets.’ Those opposed were ‘dry.’ The question took on added significance in a city that was once known as Hickory Tavern, founded on an available drink, a meal and a night’s stay after a long day’s ride into the western North Carolina wilderness.

Just a few years after incorporation and subsequently dropping ‘Tavern’ from Hickory’s name, some Hickoryites thought spiritous drink (and the behavior that went with it) were unfit for a town being heralded as a kind of “Eldorado.” They got to work re-crafting Hickory as a more upstanding place, untying it from its wild-west past and turning it into one of the Tarheel state’s most prosperous and promising municipalities.

Closing the saloons in town required much more than just a belief that it should happen. From pulpits, street corners and ultimately stump speeches, dry forces painted a picture that giving up drink was the sure-fire way to help Hickory progress. They asserted that towns like Concord, at one time comparably sized, had grown twice as large, because they banned the bottle.

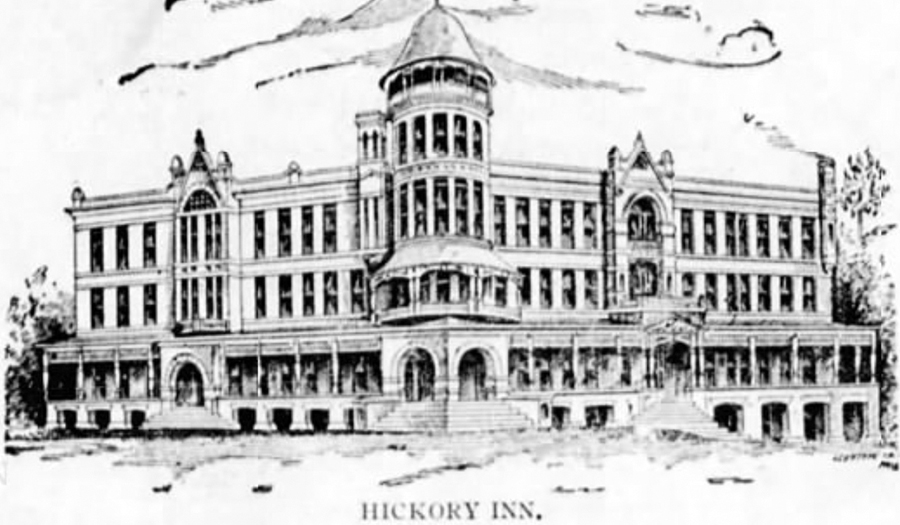

Photo: The elegant Hickory Inn, during its tenure located just south of the railroad tracks. The hotel was instrumental in keeping Hickory wet in 1889, le.

Wets fired back. They argued that “drinking will be done in the dark,” out of the view of the law, and more importantly without being taxed, thus robbing local school children of much needed funding for their schools. If the fight proves anything, it’s that a community can find any number of issues to fight over.

Down in Raleigh, the General Assembly fumbled with the question, voting in 1873, the year Hickory became tavern-less, to give municipalities a local option to vote out booze. Up in Marion, the drys prevailed but the “Old Fort Whiskey Shop” refused to shut down. In the words of one newspaper, “a civil war is threatened.”

A few years later, a referendum on the question went to voters across the state. When the ballots were counted, most North Carolinians said “NO,” loudly. By a 3-1 margin, getting rid of alcohol was defeated. The 1881 vote came 30 years after the state of Maine, first in the nation, prohibited all spiritous drink. They kept it going until after national Prohibition was over, though illegal barrooms still operated.

Local Hickory adherents to temperance did not accept the defeat easily. In 1889, during elections for mayor and council, voters knew who was wet and dry, voting their choice accordingly. The Board of Aldermen split evenly, leaving the deciding vote up to the mayor, who broke ties. Anti-liquor advocate J.G. Hall won the mayor’s job by a razor-thin 5 votes and as Hickory Press editor John F. Murrill said about him, “we hope all know where the mayor is” on the question.

It looked as if Hickory was on the verge of banning liquor from its offerings. Aldermen took a vote. The result was as expected. What surprised everyone was that one of the drys asked for a recount. He had a change of heart. Instead of going dry, Hickory remained wet, 4-2. The vote reflected the wish of the largest entertainment establishment in town, the grand Hickory Inn, who thought the hotel needed to include the availability of a good, stiff drink.

No doubt, the drys were as mad as a hatter over the switch. They vowed revenge and they would get it.