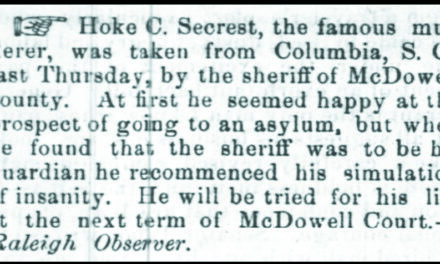

The remnants are there. If you stand in downtown Hickory and looked around, you recognize that once, the city was obviously a railroad town. Certainly, the tracks splitting north from south are a good indicator. However, the fact that Union Square orients itself toward those tracks with the passenger depot on the other side, clues you into the focus of the town’s early life. From where they now stand, it’s easy to see the row of buildings bow to Hickory’s railroad roots.

Along with the tracks, the station remains the last artifact of its past. As late as the 1960s though, there was a lot more to remind you. A freight depot once stood on the east end, plus a variety of sidetracks allowed for switching cars right when shoppers were heading downtown to conduct a little business. Maddening for those who grumbled at the delays. Crowded? Inconvenient? Yeah, but a distinct time in Hickory’s evolution.

And yet, when it all went away and functioned much more like it does today (traffic tie-ups from just automobiles), folks missed the sideshow of the sidetracks. For over a century (1870s-1970s) when trains were such a nuisance, residents had listened and learned the whistles and chugs of the locomotives. Those noises told them exactly what was happening, even if they stood miles away. It was a language to which they had become familiar.

Coming into the station, railroad procedure required engineers to signal their approach. Two long blasts, followed by a short one indicated a crossing. Over decades, residents got used to the sound and could set their watch by it. Quickly, they learned from which direction the train came (five long blasts signaled arrival from the east, four from the west). A short toot heralded a stop. Two told everyone that it was moving on. A series of blasts warned of an emergency on the tracks. The notes of each day’s song poured out over Hickory, chronicling the whirl of activity on Union Square.

Hickoryites even began to recognize the signature blasts of individual engineers too, if they listened closely. On their daily runs, experienced train drivers routinely replaced standard steam whistles with their own. They pulled the cord much like a musician plays an instrument, sounding out a unique melody. In fact, some engineers became so skilled that listeners swore they heard the old gospel tune, “Oh Happy Day” ringing out all over town. Others though, thought the driver was playing the popular barroom ditty, “How Dry I Am”, instead.

Even the steam sang a song. The percussive chugs of the coal-fired engines echoed every stage of the journey, telling residents what was going on without even seeing the train arrive or depart the station.

After diesel locomotives took over in the 1950s and trains moved from the center of everyday life, the noise began to die down. The sound of Hickory became more subdued. All that could be heard was the occasional car horn or the cranking of engines as motorists concluded their downtown chores. Nostalgic residents began to miss the daily cacophony of steam blasts that once tippled out from the center of town. By then, it was too late.

Like a lost song, the melody sat waiting, perhaps never to be played again.

Photo: Union Square. For over a century, the row of buildings stood waiting to hear the call of the trains as they rattled by.